CONCRETE GRINDING

Surface preparation is the most important part of any acid-stained concrete flooring project. For the project to hold up over time, you must begin with concrete that is clean, dry, and sound. Unless it's a brand new slab, this often means removing tile adhesive, drywall mud, carpet glue, or paint - often a combination of these residues. Even if the concrete has not been treated, or received some sort of floor covering, there is still almost always a great deal of drywall mud, paint, primer, foam insulation overspray, hydraulic fluid, glue, and other construction adhesives and chemicals found on the concrete that mars and obscures the surface. Builders and tradesmen on tight time schedules rarely take time to protect what they see as "ordinary" gray concrete.

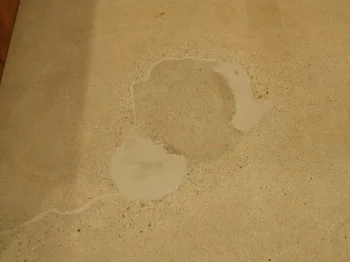

This concrete floor was ground with a 7" diamond cup grinder to remove a thin sealer in preparation for a new coating. The uniform, off-white appearance is how concrete should look after cleaning.

Getting a concrete floor clean enough to stain may mean using a variety of methods, ranging in aggressiveness, depending on the age and condition of the concrete. Concrete diamond grinding is the most common method method. Done properly, it shaves off whatever is on the surface, plus a little bit of cement, while affecting the concrete as a whole, as little as possible. Materials like carpet glue, tile adhesive and paint, generally always need to be ground off. Chemical strippers are sometimes effective in removing tacky or sticky adhesives that clog grinders, so they may be helpful at the outset of a project, but they will not get all residue off the concrete, and usually need to be followed by light grinding. Also, while chemical strippers may be effective in removing thin layers of paint and sealer, and isolated areas of adhesive, the oils and solvents in these strippers often permanently stain or darken the concrete, as do carpet glue and tile adhesive themselves. Diamond grinding is the best way to remove all traces of a foreign substance from the cement surface of a concrete slab without compromising its integrity for acid-staining the concrete.

OTHER CONCRETE CLEANING METHODS

Shot-blasting was required to clean this concrete patio, before resurfacing with an overlay, because of the rough texture and longstanding dirt and discoloration.

More aggressive methods to clean concrete, such as shot-blasting and scarifying, are required for removing thicker, harder layers of material, like epoxies, gypsum-based underlayments, thinset mortar under ceramic tile, and raised concrete "caps" covering up electrical or plumbing repairs. Shot-blasting or scarifying may also be necessary to clean concrete with a very rough texture, lots of pits and valleys, or deeply embedded staining. One problem is that these two cleaning methods compromise the cement surface of a concrete floor, leaving ridges or "row" marks. They also leave micro-cracking in the surface of the concrete. Therefore, shot-blasting and scarifying usually need to be followed by grinding to smooth and stabilize the surface. The use of these methods may also subsequently require a thin cement overlay to resurface the concrete, and cover scratches, furrows, pits, valleys, and exposed aggregate.

This new basement concrete floor looks to be pretty clean. But the rectangular area under the stairs, where drywall sat prior to installation, shows how much work really needed to be done to clean this floor.

Getting concrete clean does not always require an aggressive method like grinding, shot-blasting or scarifying. If concrete has not previously been treated, scrubbing with a rotary floor machine, using a black or purple stripping pad, cleaning detergent, and warm water can also be quite effective. A couple passes in crisscrossing directions will usually get up the majority of dirt, dust and drywall mud. Anything left behind will then show up clearly enough on the wet surface of the concrete, and be sufficiently softened, so as to be scraped off with a 4" wallpaper razor scraper, or wire brush. An angle grinder fitted with a lightly abrasive sanding disc can also be used for spot removal. Some blemishes caused by chemicals and solvents, like “liquid nails”, during the build-out process cannot easily be detected during cleaning, and usually only show up clearly during the concrete staining process. These types of blemishes can best be removed by engraving them out with a Dremel-type tool, and then touching up with stain; or through "faux finishing" using artist tints.

CONCRETE REPAIR

Making concrete sound enough for the installation of acid-stained or other types of decorative concrete flooring, like polished concrete, metallic epoxy and cement overlays, will generally mean using one or more of these three repair applications: 1) patching small holes, pock marks and divots; 2) repairing cracks; and 3) rebuilding damaged or missing sections of concrete.

The patching of these tack strip holes in this acid-stained bedroom concrete floor, though clearly visible, disappeared completely after applying the clear sealer.

Patching is necessary on almost every concrete floor prior to staining. Small chips or missing pieces of concrete are commonplace, and overall, they may look "natural" enough, and so inconspicuous, as not to need to be addressed. But larger areas, like sections of "spalling", and half-dollar-sized holes left by nails from carpet tack strips or the removal of anchor bolts, do stand out. Patching this type of damage can effectively be done with cement- or epoxy-based grout repair materials. But these materials require at least several hours to dry; and in some cases need to sit overnight. This may not present a problem, if there is a great deal of patching to be done that takes a good part of the day. But if it's only a small amount, and the next step of a flooring project needs to proceed quickly, there are specialized, two-part urethane- and polyurea-based repair products than can be used, which are typically mixed with sand and dry in a matter of minutes. These materials often can be mixed with pigment to blend in with the stain to be used on the project.

These settlement cracks in a basement concrete floor were repaired using epoxy. After drying overnight, excess material was ground off and an overlay installed. The cracks did not return.

Cement- and epoxy-based grout repair materials can also be used to repair cracks, but since crack repair is almost always a two-step process, urethane- or polyurea-based repair materials are preferred. They set up much more quickly, and the second step of the process - removing excess, or overflow, material from the surface - can begin almost immediately. There are two categories of urethanes and polyurea crack repair materials: 1) "structural", for stable cracks; and 2) "semi-rigid", for cracks that may continue to move. The excess material from structural repairs cures so hard that it must be ground off, while the excess material from semi-rigid repairs remains somewhat flexible, and may be shaved flush with a long-handled razor scraper.

This was a complicated repair that involved structural patching and crack repair. The repair was so large that it also required a cement overlay to cover it up, after installing a crack isolation membrane so that the overlay wouldn't crack.

Damaged or missing sections of concrete are most commonly encountered on indoor acid-stained concrete flooring projects along, or at the intersection of, joints. On outdoor acid-stained concrete projects, like patios, driveways or pool decks, they are often also found around the periphery of a concrete slab. Large repairs like this may be done with either straight cement, or specially engineered repair mortars, that are based on cement, epoxy or polyurea. Cement, and cement-based mortars, are inexpensive, but they can take a long time to cure. Epoxy- and polyurea-based repair mortars dry much faster, and have much better long term durability, but they are more expensive and difficult to use.

Lastly, since patches, crack repairs and rebuilt sections of concrete usually do not blend in color with the main body of a traditional, gray concrete floor, it is often important to mix color, such as color hardener, powdered pigment, or liquid colorant, with the repair material beforehand, if the concrete floor is going to be decoratively stained. That way, remaining imperfections from the repairs may not stand out, or faux finishing techniques may easily be used to conceal them. Even if the repairs do stand out, for example after large, saw-cut plumbing and electrical repairs or upgrades, the overall appearance may not be objectionable, if the repairs are few in number. The repair outlines also can be incorporated into the overall design of the floor. Much of the structural damage that happens to a concrete floor occurs during the build-out process, and may be prevented by using a temporary, protective floor covering, like Ram Board.